After several thousand years of domestication it’s inevitable that a certain degree of anthropomorphism has crept in to the relationship that we have with our domesticated animals. And perhaps, like familiarity, anthropomorphism breeds contempt. Or, if not contempt, then at least a certain degree of complacency. After all, when we only ever view animals with our anthropocentric glasses on they seem like lesser versions of ourselves. They can’t talk, they can’t drive cars, they can’t update their Facebook status. But what an anthropocentric perspective fails to acknowledge is that if the boot was on the other foot (or paw) it would be us who were lesser versions of them. How slowly we run. How blind and deaf we are. How badly we fly.

0 Comments

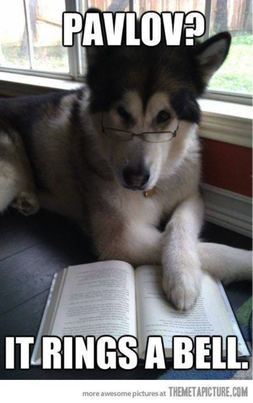

We really like our bitless bridles and use them for many reasons. They can help improve calmness, jumping technique and self carriage. They are great for riders that can’t stop fiddling with the reins and they teach us a great deal about how each individual horse likes to carry his head in order to have the best vision. But mostly we use our bitless bridles because they provide a training task that is different to everyday and because it’s great fun to ride bitless. Read part one of our going bitless articles here. We use our own design of bitless bridle because they are simple, there is no time delay between the release of the aid and the release of the pressure, and it’s very compatible with the aids that we train during groundwork. Basically, our bridle is a cavesson noseband with reins attached to the side. We have always found it to be simple and the transition from bit to bitless is really quite straightforward. You can purchase a Sustainable Equitation Bitless Bridle here.  Lots of people like the idea of riding bitless but are not completely sure where to begin or if it’s worth the time and effort required – not to mention the extra expense of another piece of gear. However, the transition to bitless riding is not only relatively straight forward it is also a great way to enhance your horse’s training and can help develop calmness, improve self carriage and also fine tune jumping technique. We use a bitless bridle on all of our own horses – not all of the time, but usually at least once per week. Any training they can do in a traditional bridle; they can also do in a bitless one. So, they will jump, cross country school, do working equitation obstacles, dressage and general fitness work in their bitless bridles.  It’s pretty hard to set out to train an event horse. In reality what you have to do is pick a nice horse and start training. You might end up with an all-rounder, a pony club horse, an event horse, or anything else in between. I believe that regardless of your discipline, you should aim to improve your horse. Improve him physically and nurture him mentally and whether you end up with an Olympian in your chosen discipline or a fabulously safe all-rounder, you’ve done well.  The recent controversy in the press and on social media regarding the tightness of nosebands has been thought provoking. While any equestrian debate that questions the welfare of age-old practices is destined to be clouded by emotion and the anthropomorphic belief systems that underpin modern horse management, objectivity is a necessity when trying to balance the views of both die-hard traditionalists and an increasingly informed animal rights movement. It is hard to fault the scientific credentials of the team behind the study that has caused so much controversy. It was conducted by the University of Sydney's Faculty of Veterinary Science and senior author Professor Paul McGreevy is a veterinarian, author and past winner of the Eureka Prize. A quick look at McGreevy's list of publications shows that he is passionate about welfare issues and unafraid of shining the light of scientific objectivity on a practice that is older than the wheel. In this study, twelve horses unaccustomed to wearing a double bridle and a noseband showed easily identified stress markers (which included an increase in eye temperature and heart rate) when that noseband was tightened to the point that a finger would not fit between the noseband and the horse's nose. The horses in the study also showed a marked decrease in the number of oral behaviours that they performed (such as licking, chewing and swallowing) while wearing the noseband.  I was thinking today about the concept of obedience and how, in our society, the word has acquired some negative connotations. Without contemplation I wouldn't want to have been described as obedient, nor would I have felt pride as a parent if my children were described as obedient. I think the term has become synonymous with subservience and submission and that there is an unspoken suggestion that compliance has been achieved through coercion. Yet, I have to say that most of us are obedient when we consider the word in its true sense. We don't slap people who annoy us, we pay for things and we drive on the left side of the road. My children don't steal the lunches of other kids or hit their teachers or kick the dog. Most of us are obedient to the rules that govern the country in which we live. Generally speaking, when people break those rules it's because they are unhappy or disenfranchised or desperate. It may sound disingenuous, but losses of obedience rarely lead to happiness. This of course does not mean that we cannot question the world in which we live or the way in which it is being run. Obedience should not entail censorship. As adults it's ok if we just don't break the rules. Obedience should not mean that we are controlled by another adult. Or punished. Or threatened. The rules that govern society function to enable everyone to live in relative peace and safety. The kind of bullying that is at work when one person oppresses another, usually functions to maintain an already skewed balance of power. That's the kind of tyranny and oppression is the symptom of a disease that is endemic in our society.  Bob Bailey is a pretty amazing guy. With his wife, Marion Breland, he owned and ran Animal Behaviour Enterprises and together they trained over 15,000 individual animals from 140 different species to do pretty much anything you can think of. I really like Bailey's work, I often turn to it when I can't see the way forward or just want a bit of inspiration. He has a way of stripping off all the anthropomorphism, superstition and emotion and just getting down to the core issues. One of the most profoundly interesting things I have ever read about training and yet one of the simplest is something that he wrote, "You get the behaviour you reinforce, not necessarily the behaviour you want." Bailey takes any responsibility away from the animal being trained and gives it all back to the trainer. I think this a common thread that you see throughout the work of really good training theorists. Own your failures, not just your successes. (Andrew McLean is the master of this approach, though Andrew always gives you the feeling that he sympathizes with and understands your human frailty. Bob Bailey is perhaps more blunt but he's not primarily a coach, he's an animal trainer.)  Ivan Pavlov was a Russian scientist. In the very first years of the twentieth century he conducted experiments on the digestive systems of dogs, trying to determine how they worked. Every day, Pavlov's assistant would bring meat into the laboratory and he would feed the dogs and measure the amount of saliva and gastric fluid that they produced. The assistant's trolley had a squeaky wheel and Pavlov began to notice that, after a while, the dogs started to salivate as soon as they heard the trolley squeaking down the hallway. Pavlov was fascinated by this phenomenon and he started to explore the psychology of expectation. He rang a bell before giving the dogs their meat and after a few repetitions dicovered that just the bell on its own would cause the dogs to salivate. What Pavlov had discovered we now know as classical conditioning. Classical conditioning occurs when a previously meaningless stimulus (like a bell) becomes paired with a known response (like salivation). It explains why you feel happy when you smell the perfume of someone that you love, why you duck when you hear a loud noise, why your dog barks when he hears your car coming up the road and why your horse will trot across his paddock towards the sound of a carrot being snapped in half. Classically conditioned cues piggy back onto existing ones and can also piggy back on classically conditioned cues that are, in turn, piggy backing on existing responses. Each and everyone of us is a swirling hodge podge of classically conditioned cues and reponses that psychologists would refer to as antecedents, and this is part of what makes us such complex and interesting beings. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed